Ukraine: The Struggle for Power and Identity

Ukraine: The Struggle for Power and Identity

The decision of the Ukrainian president to turn away from the European Union has led to mass street protests. But that decision was only a triggering event, not the main motivation for the current unrest. Despite the mass media's presentation of the current situation in Ukraine as a conflict between a pro-Russian government and pro-European anti-totalitarian popular opposition, the reality is much more complex and multilayered. One dimension is ethnic and regional differences in the perception of the nation and the contested and controversial process of imagining a national community. The second dimension is antagonism of the people and the government in the extremely poor economic conditions, corruption, and impoverishment of the population. The third dimension is a contradiction between liberal ideology of the emerging civic society and primordial positions of the majority of the population. And finally, the fourth dimension is the support of, or opposition to, the influence of Russia on Ukrainian politics, economy, culture, and social processes.

The decision of the Ukrainian president to turn away from the European Union has led to mass street protests. But that decision was only a triggering event, not the main motivation for the current unrest. Despite the mass media's presentation of the current situation in Ukraine as a conflict between a pro-Russian government and pro-European anti-totalitarian popular opposition, the reality is much more complex and multilayered. One dimension is ethnic and regional differences in the perception of the nation and the contested and controversial process of imagining a national community. The second dimension is antagonism of the people and the government in the extremely poor economic conditions, corruption, and impoverishment of the population. The third dimension is a contradiction between liberal ideology of the emerging civic society and primordial positions of the majority of the population. And finally, the fourth dimension is the support of, or opposition to, the influence of Russia on Ukrainian politics, economy, culture, and social processes.

First, independent Ukraine inherited an unfinished process of nation-building complicated by historic, cultural, ethnic, and linguistic differences between regions. The contestation of Ukrainian national identity impacts internal conflicts between ethnic and regional groups. Undefined Ukrainian national identity influences foreign policy and defines the vector of international relations, including relations with Russia and the European Union.

Second, the absence of a clear national idea is strongly interconnected with the democratic and economic development of Ukraine. The promise of president, Yanukovich, to combat corruption as a major problem in Ukraine was never fulfilled: glaring conflicts of interest among senior officials, combined with delays in the passage of anticorruption legislation, fueled public skepticism about the leadership’s ability to combat graft in 2010. According to Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index, Ukraine’s rank among the 178 surveyed countries changed from 134th in 2010 to 144th in 2012. The Heritage Foundation’s 2013 index of economic freedom put Ukraine in the 161st place out of 177 surveyed states. Forbes placed Ukraine in the fourth place among the world’s worst economies.

Third, the national identity is deeply rooted in ethnicity and culture while the civic foundations of national identity are less developed. Based on the legacy of Soviet ethno-federalism and the incorporation of ethnic identity into the state passport system, the development of the nation has become perceived in ethnic terms. Democracy is very weak and civic society is still in an embryonic state, having virtually no influence on the government.

Finally, Ukrainian identity depends on the establishment of a clear distinction from Russia, at the same time this identity remains closely tied to Russia. It is extremely sensitive to changes in Russian policy. The arrogant imperial actions of Russia strengthen the divide between the two countries while economic cooperation increases positive sentiments toward Russia. While in 2012, 83% of the Ukrainian population had positive attitudes toward Russia (with regional differences of 91% in Eastern and Southern regions and 63% in Western regions), only 14% wanted to reunite with Russia.

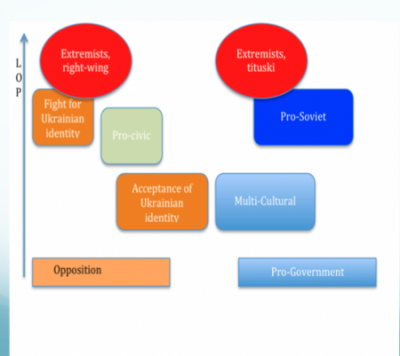

This complexity of issues is reflected in the high heterogeneity of the opposition. There are several opposition groups with very different narratives. The most active is the group promoting the “Struggle for Ukrainian Ethnic Identity.” They describe Ukraine as a homogenous culture of ethnic Ukrainians with enclaves of pro-Soviet Russians that have resulted from colonization and immigration. Ukraine for them is a post-colonial, post-genocidal society that was able to survive, preserve its culture and language, and achieve independence. They believe that Ukrainian culture, language, and history remain under threat from the pro-Soviet population and the present government, which is supported by Russia. The major divide in the society is between authentic Ukrainian democratic values and pro-Soviet Russian totalitarian ideals. They join the opposition to protect Ukrainian language and history from pro-Soviet influences and to create policies that empower the Ukrainian ethnic group. Some of this group, including members of the “Svoboda” party, are involved in extremist actions.

They are joined by a group that promotes Ukraine as multicultural civic state with coequal ethnic groups that should build a civic, not ethnic, concept of national identity. This society for them is the product of the efforts of all Ukrainian citizens, united by the idea of independence. They see the threat to their ideas from both Ukrainian and Russian nationalists as well as the pro-Soviet population. They protest paternalistic and totalitarian government and believe that Ukraine’s common identity should be grounded in inclusive ideas of citizenship and should reflect the plural voices of Ukrainian history.

The third group that forms the opposition shares the narrative “Recognition of Ukrainian Ethnic Identity.” They see Ukraine as a homogenous culture of ethnic Ukrainians with small ethnic minority groups: Russians, Crimean Tatars, and Hungarians. The society is united by the deep democratic traditions of Ukrainian culture, which differs from Russian totalitarianism. The Russian-speaking population enjoys sufficient opportunities in Ukraine; tensions are provoked only when Russia is trying to manipulate the issues. They are on the streets to defend Ukrainian independence from the Russian influence in politics, economics, and culture in Ukraine.

The population that supports the government is also heterogeneous. One group supports a vision of Ukraine as a country with a dual identity comprising two coequal ethnic groups. People supporting this narrative are proud of their Ukrainian-Russian culture and heritage, see the country as divided by regional differences, and believe that Ukrainian nationalists are the ones responsible for escalating tensions in the country. They see the opposition as a threat to the Russian language and culture as well as the position of Russians in the structure of power.

The second pro-government group professes a pro-Soviet narrative and provides positive assessment of the history of the Soviet Union. Ukraine is thus portrayed as a multicultural society where all internal conflicts are provoked by nationalists. They believe that Soviet Ukraine was a tolerant brotherly nation based on the common identity of the Soviet people (Sovetskii narod), but now nationalists are imposing their vision of history and society on the whole country and are ruining the peaceful nation. Some of the most extremist pro-government activists belong to this category and some, including the “Tatuski” group, are being paid by the country leadership.

To address this complexity and mitigate the conflict, it is important to introduce both agonistic dialogue and develop a shared society. Agonistic dialogue rests on the ideas of agonistic pluralism that converts antagonism into agonism that implies a deep respect and concern for the other, promotes engagement of adversaries across profound differences, and involves a vibrant clash of democratic political positions. In divided societies, agonistic dialogue becomes an essential practice that contributes to building relationships and expands understanding between groups. Dialogue in divided society should not illuminate conflict, but rather transform the nature of that conflict. Thus, agonistic dialogue practice is less about finding the ‘truth’ or some form of consensus about the history of the conflict, but rather about seeking accommodation of conflicting positions.

To address this complexity and mitigate the conflict, it is important to introduce both agonistic dialogue and develop a shared society. Agonistic dialogue rests on the ideas of agonistic pluralism that converts antagonism into agonism that implies a deep respect and concern for the other, promotes engagement of adversaries across profound differences, and involves a vibrant clash of democratic political positions. In divided societies, agonistic dialogue becomes an essential practice that contributes to building relationships and expands understanding between groups. Dialogue in divided society should not illuminate conflict, but rather transform the nature of that conflict. Thus, agonistic dialogue practice is less about finding the ‘truth’ or some form of consensus about the history of the conflict, but rather about seeking accommodation of conflicting positions.

The development of shared power and shared society will ensure legitimacy of the new government. A simple transfer of power to the opposition will lead to a new swing of pendulum and decrease its legitimacy for Ukrainian population. The new government should be formed as a coalition of all parties and major groups in Ukrainian society and should promote the idea of shared society. A shared society supports equality of all cultural, ethnic, and religious identities, recognizing their values and interdependence. This approach addresses divisions between groups and creates positive connections between communities. Accountable governments and inclusive decision-making, including administration, representative bodies, an accessible judicial system, free and fair elections, and equal access to basic services, help develop trust and positive social engagement. The development of a shared society in Ukraine must be collaborative, adaptive to social environment, and include all stakeholders in the consensus-oriented efforts to build a peaceful and inclusive society.

### Photo 1: Flickr user Lubomyr Salamakha; Photo 2: Karina Korostelina